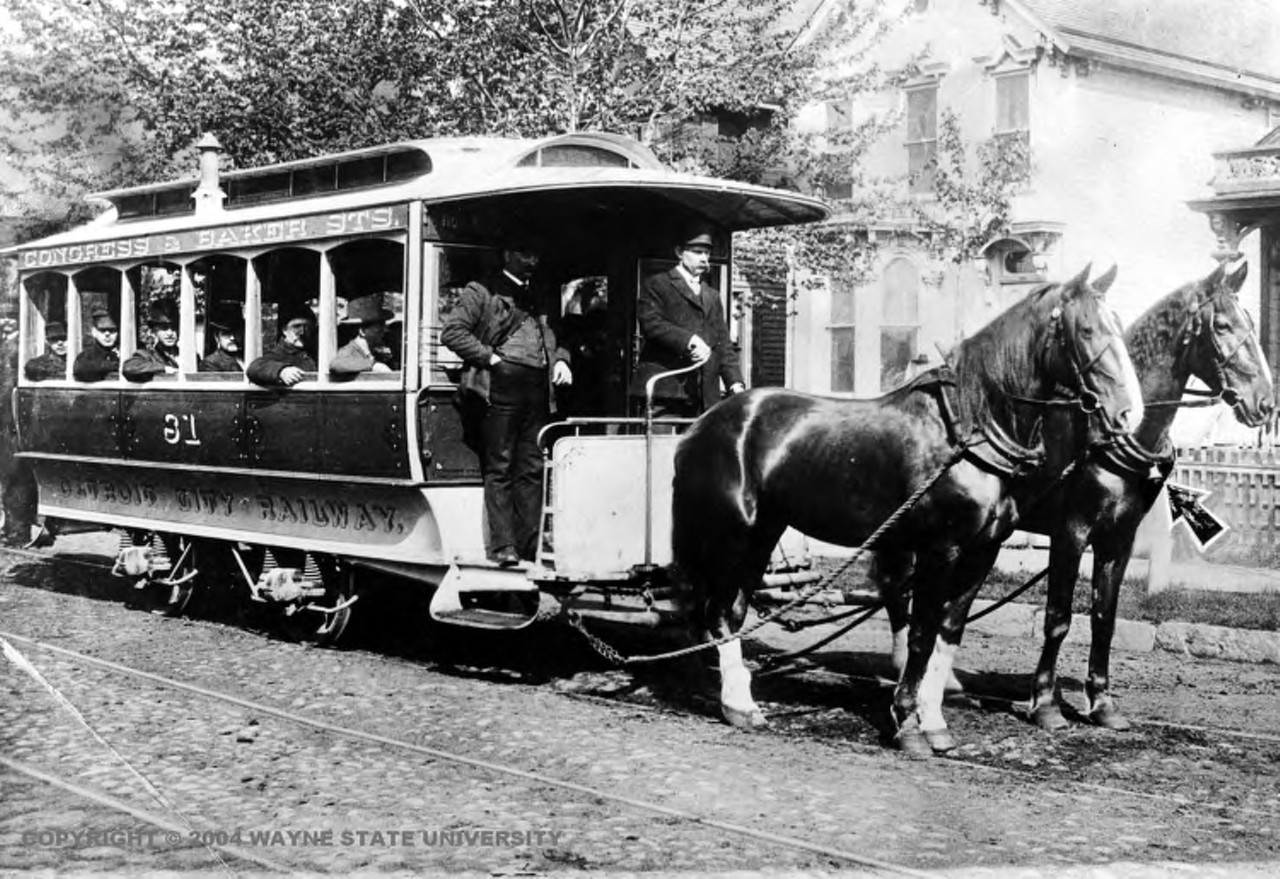

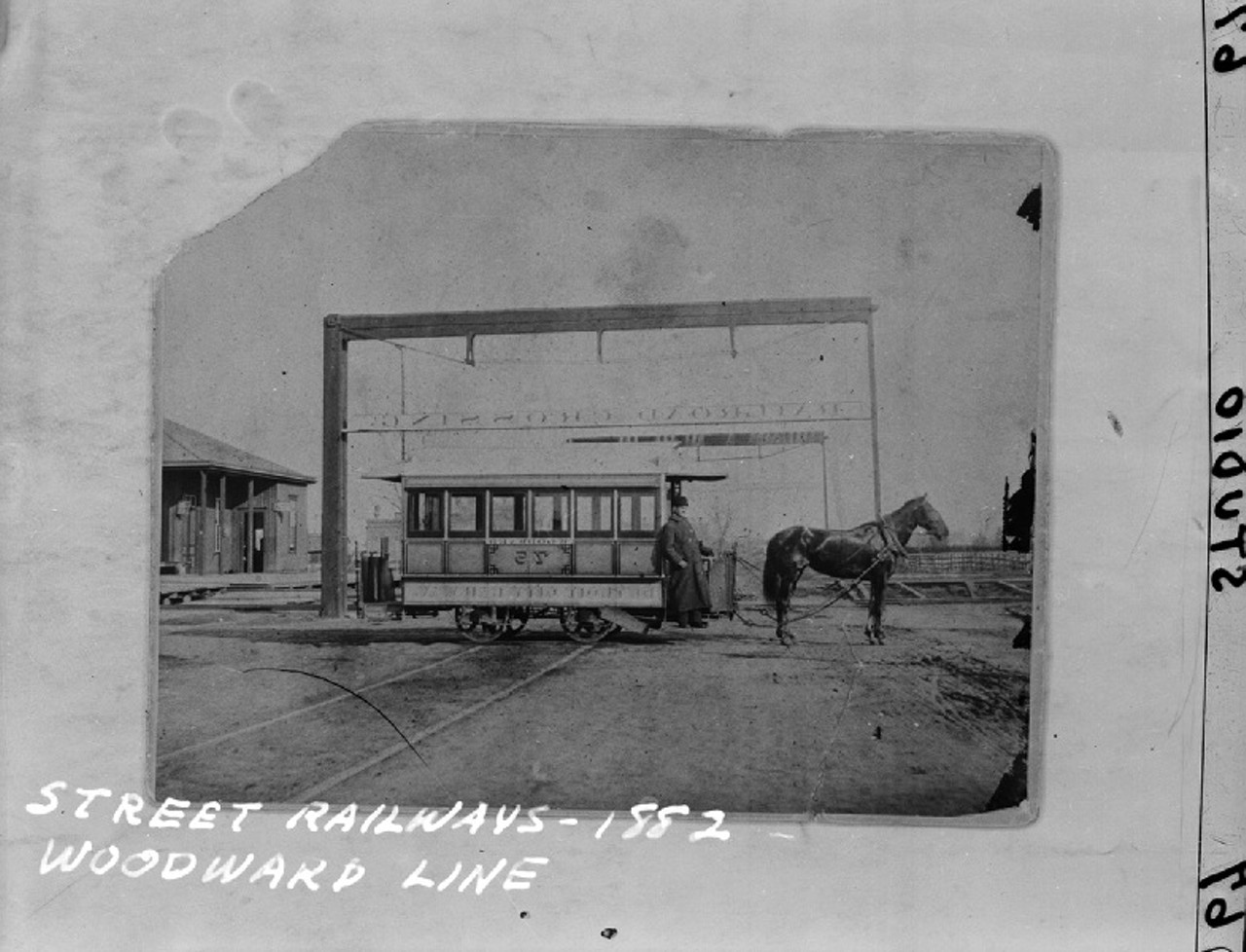

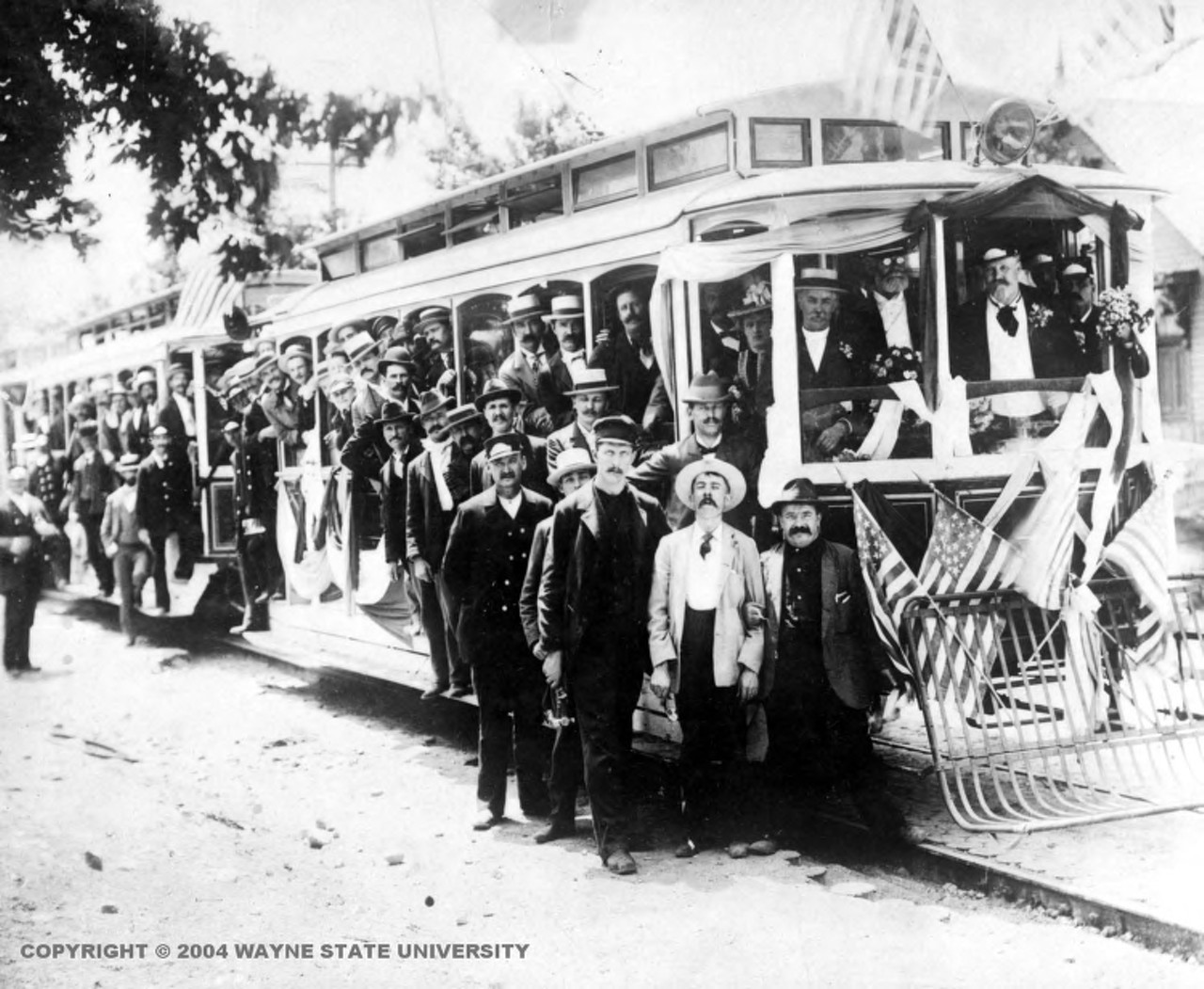

The final streetcar on Detroit's original Woodward Avenue line ran on April 8, 1956. To commemorate the ghosts of transit past, here's a nostalgic look back at the history of Detroit's streetcar system. Be sure to check out our piece on what Detroit's learned (or hasn't learned) in the 60 years since streetcars were an everyday occurrence.

This slideshow would have been impossible to make without the kind forbearance of the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University. You can see these images for yourself at the Virtual Motor City site.

Text by Michael Jackman

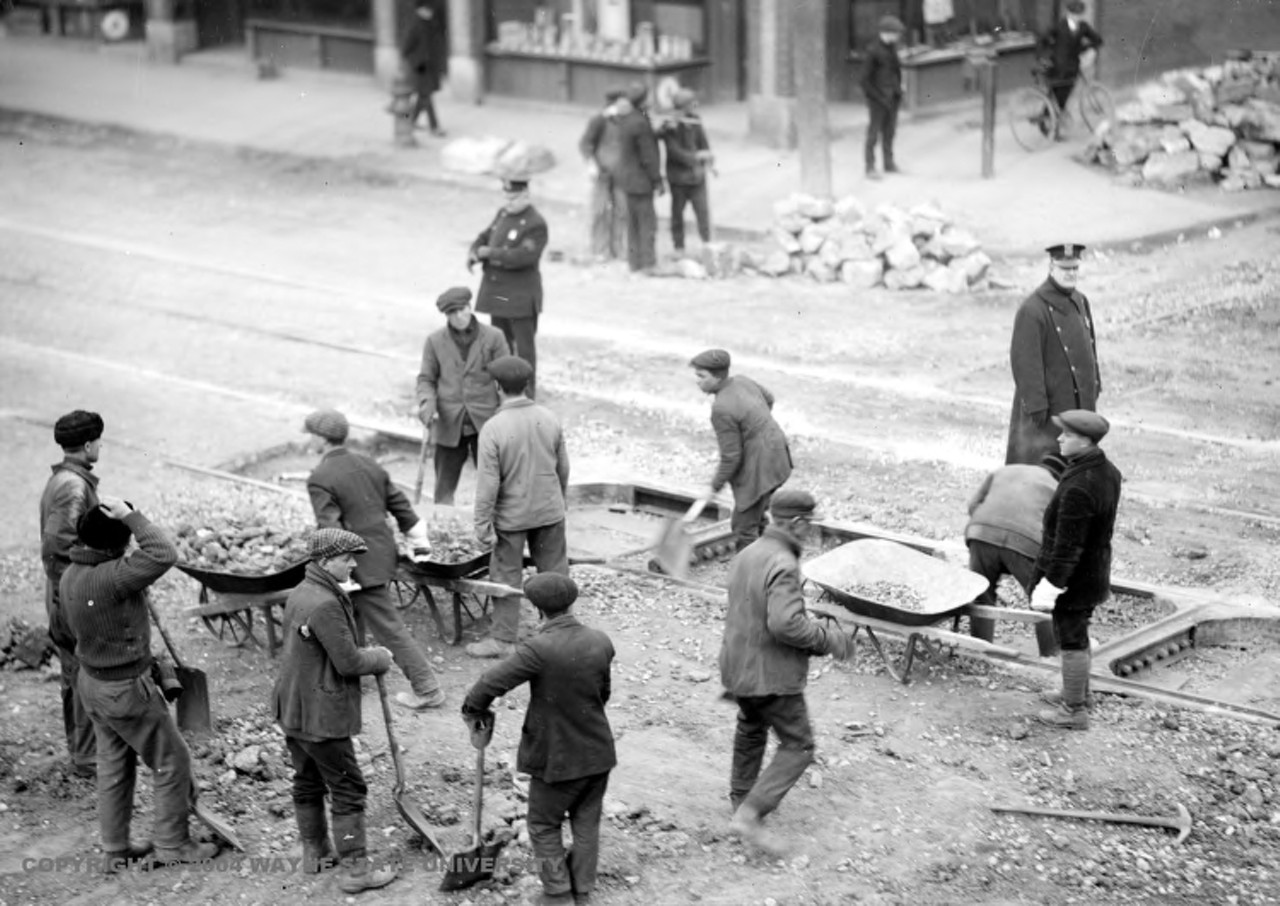

![It was a controversial move. A newspaper poll showed that Detroiters, by a margin of 3-to-1, opposed the switch to buses. Some even jeered the sunken freeways Cobo championed, dubbing them "Cobo canals." DSR historian Richard Andrews told us, "A lot of people were against the decision. There was even some agitation. A common complaint was about the sale of the [PCC streetcars], that the city didn't get its money's worth. Of course, the city had an answer for anything..."](https://media2.metrotimes.com/metrotimes/imager/19-pictures-showing-the-history-of-detroits-streetcar-system/u/zoom/29140134/pic17.jpg?cb=1647990284)