You’ve likely driven past them, walked in their shadow, or even stepped over some while paying your respects to a loved one. It’s no secret that Detroit has a deep and rich history but few know the story behind some of Detroit’s most notable (and in many cases, off the beaten path) memorials, monuments, and statues.

10 Detroit memorials, monuments, and statues you may not have known about

By Metro Times editorial staff on Fri, Jun 1, 2018 at 1:51 am

Scroll down to view images

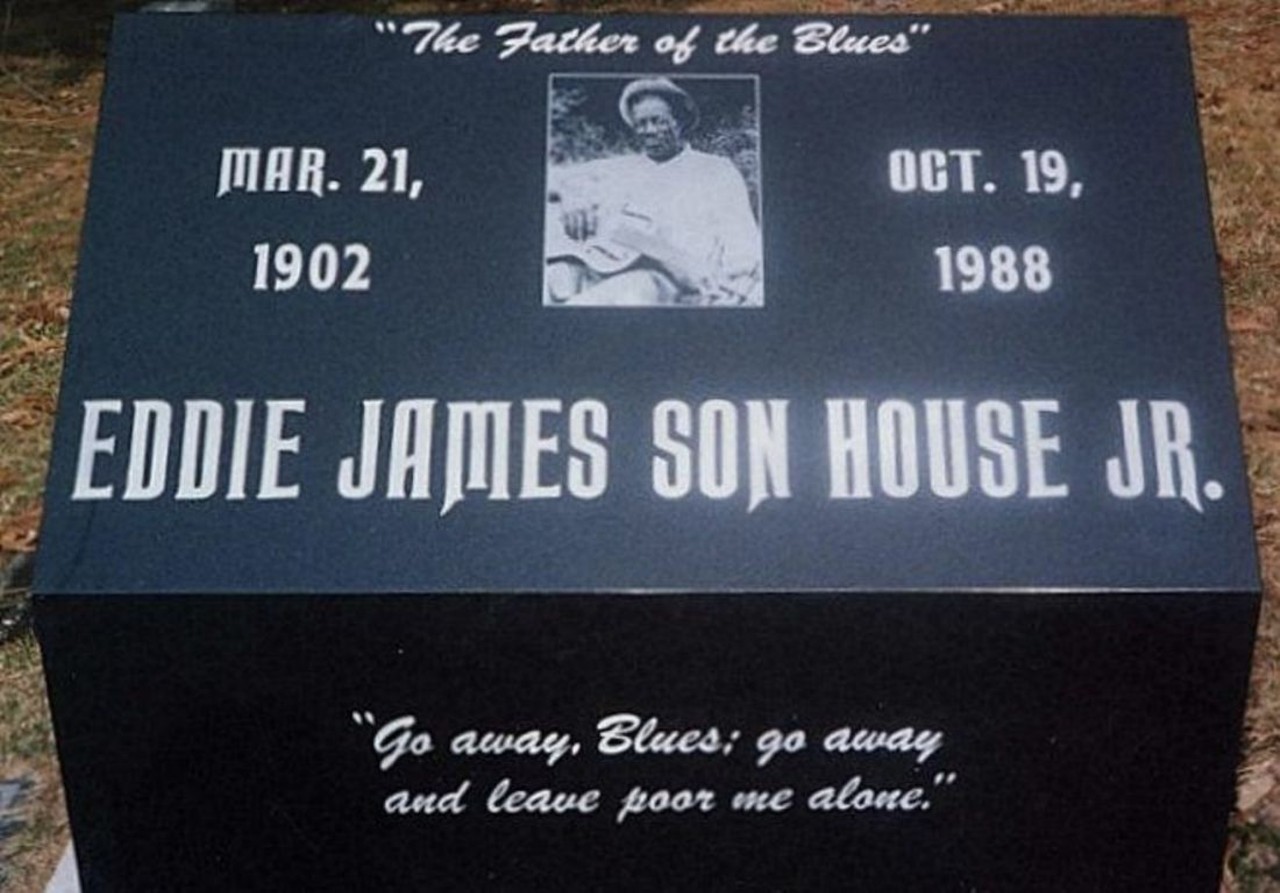

Son House’s Grave

Mount Hazel Cemetery, Lahser between Pickford and Clarita streets, Detroit

Eddie James “Son” House Jr. was born in 1902 in Lyon, Miss. When he embraced blues music at the age of 25, he was on his way to becoming one of the greatest Delta Blues musicians. He even inspired the likes of seminal bluesman Robert Johnson. House moved to Detroit late in life, in 1974, and died here of cancer in 1988. His body was buried in Mount Hazel Cemetery without a pretentious marker for many years — at least until the Detroit Blues Society helped raise money for a proper, imposing monument for this blues giant.

Photo via FindaGrave.com

Mount Hazel Cemetery, Lahser between Pickford and Clarita streets, Detroit

Eddie James “Son” House Jr. was born in 1902 in Lyon, Miss. When he embraced blues music at the age of 25, he was on his way to becoming one of the greatest Delta Blues musicians. He even inspired the likes of seminal bluesman Robert Johnson. House moved to Detroit late in life, in 1974, and died here of cancer in 1988. His body was buried in Mount Hazel Cemetery without a pretentious marker for many years — at least until the Detroit Blues Society helped raise money for a proper, imposing monument for this blues giant.

Photo via FindaGrave.com

1 of 9

Beth Olem

On the grounds of the GM Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly plant, Detroit and Hamtramck

In the early 1980s, when the Poletown area of Detroit was flattened by Detroit to make way for a new General Motors factory, one feature of the old neighborhood remained: an old Jewish cemetery named Beth Olem — in Hebrew “House of the World.” It’s still there, on the property of the enormous plant, and is open one day a year for memorial services.

Photo via CTV News

On the grounds of the GM Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly plant, Detroit and Hamtramck

In the early 1980s, when the Poletown area of Detroit was flattened by Detroit to make way for a new General Motors factory, one feature of the old neighborhood remained: an old Jewish cemetery named Beth Olem — in Hebrew “House of the World.” It’s still there, on the property of the enormous plant, and is open one day a year for memorial services.

Photo via CTV News

2 of 9

The statue of Hazen Pingree

West of Woodward Avenue and south of Adams Street in Grand Circus Park

Chances are you’ve seen the statue of “Potato Patch Ping” downtown. He’s the businessman who was run for mayor in the 1890s, only to shock his big business backers by winning and promptly becoming a progressive reformer. He was among the first to encourage urban agriculture by allowing Detroiters to use vacant city- owned lots for potato patches during the Panic of 1893. He fought the railroad and electric trusts. He helped establish public transportation in Detroit. He was elected mayor four times and left office only to become governor. The plaque on the statue reads: “He was the first to warn the people of the great danger threatened by powerful private corporations, and the first to awake to the great inequalities in taxation and to initiate steps for reform,” and calls him “The Idol of the People.”

Photo via CarriedAwayDetroit.com

West of Woodward Avenue and south of Adams Street in Grand Circus Park

Chances are you’ve seen the statue of “Potato Patch Ping” downtown. He’s the businessman who was run for mayor in the 1890s, only to shock his big business backers by winning and promptly becoming a progressive reformer. He was among the first to encourage urban agriculture by allowing Detroiters to use vacant city- owned lots for potato patches during the Panic of 1893. He fought the railroad and electric trusts. He helped establish public transportation in Detroit. He was elected mayor four times and left office only to become governor. The plaque on the statue reads: “He was the first to warn the people of the great danger threatened by powerful private corporations, and the first to awake to the great inequalities in taxation and to initiate steps for reform,” and calls him “The Idol of the People.”

Photo via CarriedAwayDetroit.com

3 of 9

Christopher Columbus Monument

Randolph Street at Jefferson Avenue, Detroit

Many didn’t realize there even was a statue of Christopher Columbus until Columbus Day 2015, when the statue was vandalized with a hatchet and splattered with red paint. Last year, a group petitioned the city to remove the statue, which was dedicated in 1910 and moved to where it stands now in 1988.

Photo via DailyKos.com

Randolph Street at Jefferson Avenue, Detroit

Many didn’t realize there even was a statue of Christopher Columbus until Columbus Day 2015, when the statue was vandalized with a hatchet and splattered with red paint. Last year, a group petitioned the city to remove the statue, which was dedicated in 1910 and moved to where it stands now in 1988.

Photo via DailyKos.com

4 of 9

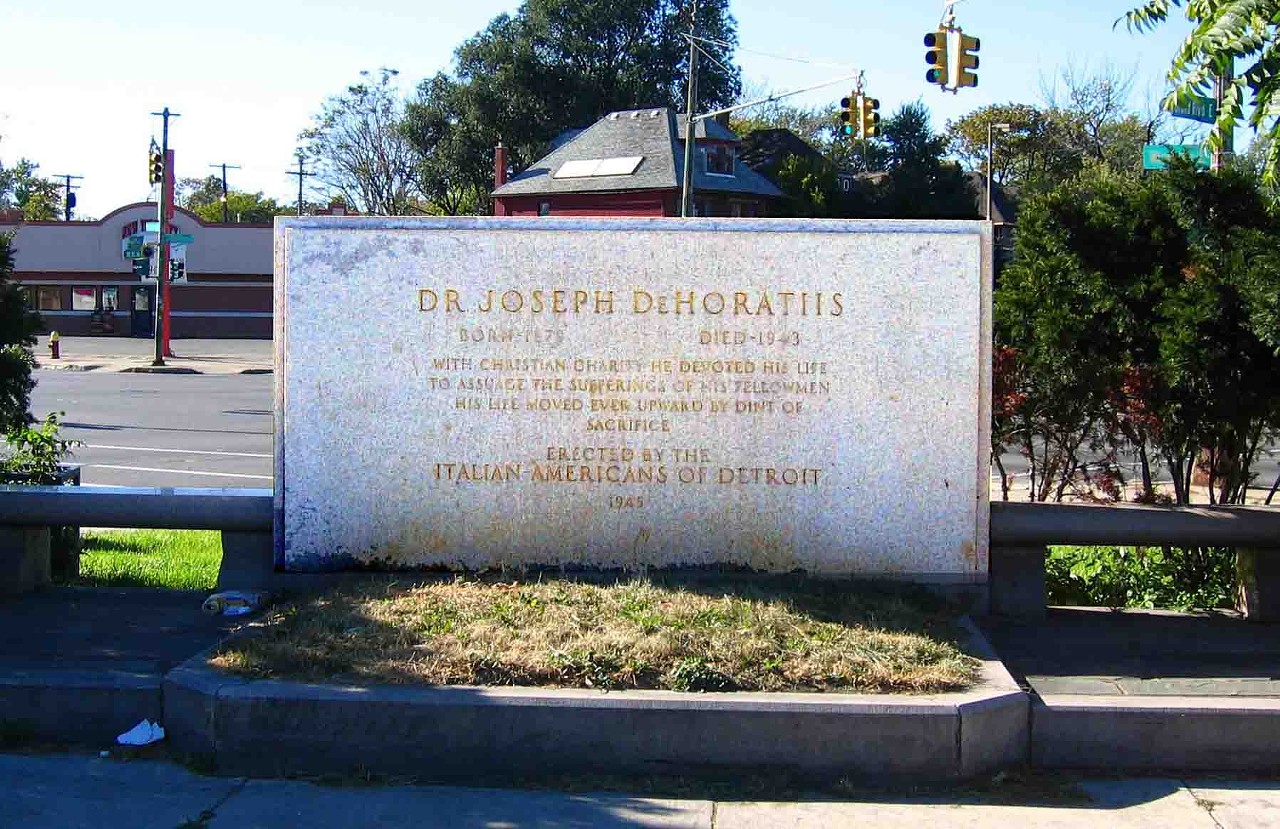

Dr. Joseph De Horatiis

Warren Avenue and East Grand Boulevard, Detroit

Born in Italy, a student of medicine in his native country and in Detroit, Dr. Joseph De Horatiis was known as the dean of Detroit’s Italian-American medical community, a decent man who dispensed advice on everything from medical matters to mortgages while servicing the immigrant community here. During Detroit’s 1943 race riot, though he had been warned by police, the doctor insisted on driving through the riot zone to treat a patient. He was attacked and killed. Detroit’s Italian-American community came together to erect this monument to the man who gave his life in service to his people.

Photo via Detroits-Great-Rebellion.com

Warren Avenue and East Grand Boulevard, Detroit

Born in Italy, a student of medicine in his native country and in Detroit, Dr. Joseph De Horatiis was known as the dean of Detroit’s Italian-American medical community, a decent man who dispensed advice on everything from medical matters to mortgages while servicing the immigrant community here. During Detroit’s 1943 race riot, though he had been warned by police, the doctor insisted on driving through the riot zone to treat a patient. He was attacked and killed. Detroit’s Italian-American community came together to erect this monument to the man who gave his life in service to his people.

Photo via Detroits-Great-Rebellion.com

5 of 9

“The Hand of God”

Gratiot Avenue east of St. Antoine, Detroit

A stark, modernistic statue in a small courtyard on the north side of the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice, the 1949 work called “The Hand of God” is actually in honor of Frank Murphy, paid for by the United Auto Workers. Murphy’s career ranged from Recorder’s Court judge in the 1920s to the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1940s, and his sympathy for the downtrodden, oppressed, and poor made him a progressive and inspiring jurist. He won the UAW’s sympathy, of course, when, in the mid-1930s, as governor of Michigan, Murphy refused to send in Michigan troops to help General Motors break the union’s sit-down strike.

Photo via DetroitVideoDaily.com

Gratiot Avenue east of St. Antoine, Detroit

A stark, modernistic statue in a small courtyard on the north side of the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice, the 1949 work called “The Hand of God” is actually in honor of Frank Murphy, paid for by the United Auto Workers. Murphy’s career ranged from Recorder’s Court judge in the 1920s to the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1940s, and his sympathy for the downtrodden, oppressed, and poor made him a progressive and inspiring jurist. He won the UAW’s sympathy, of course, when, in the mid-1930s, as governor of Michigan, Murphy refused to send in Michigan troops to help General Motors break the union’s sit-down strike.

Photo via DetroitVideoDaily.com

6 of 9

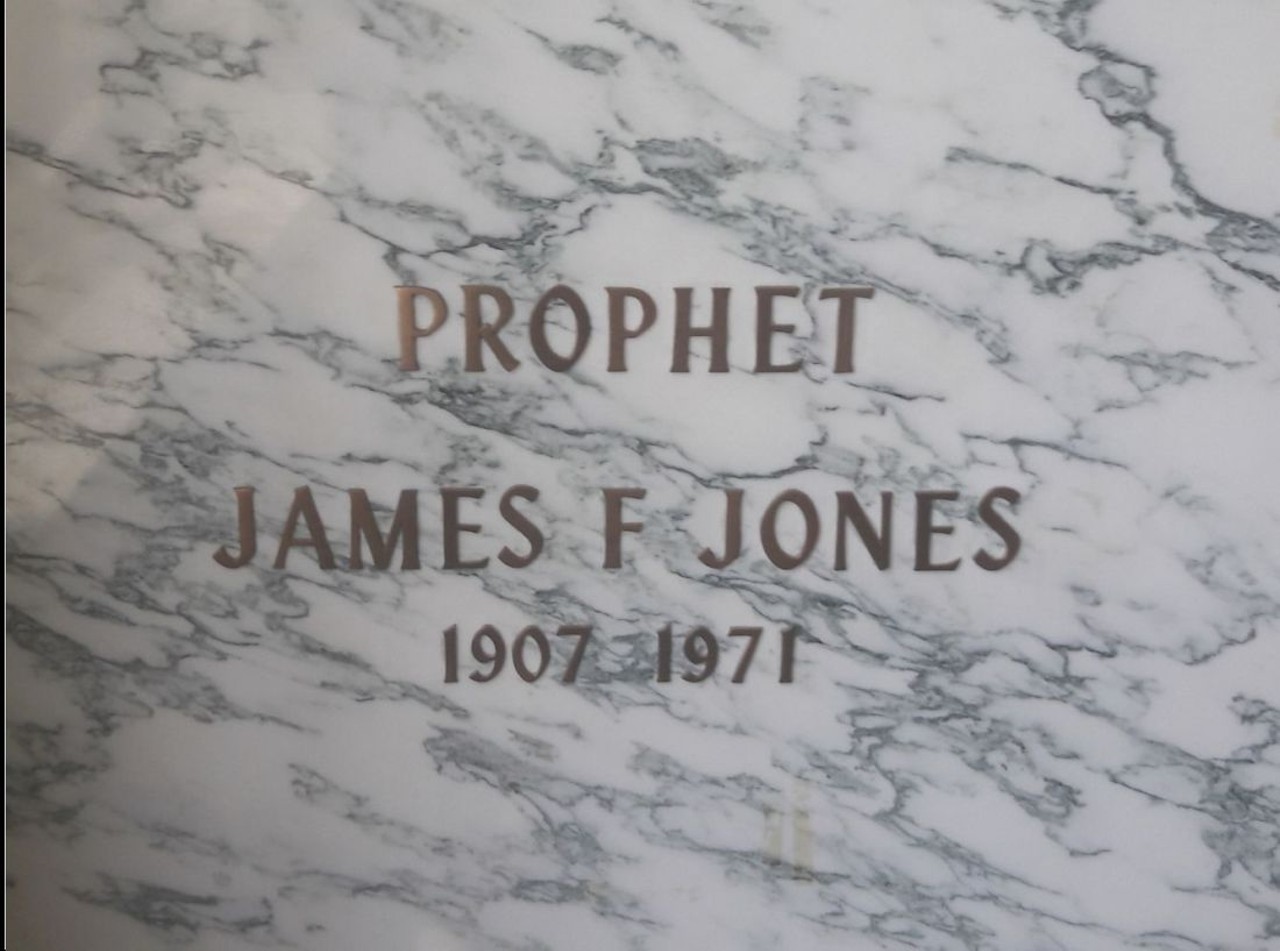

The Rev. James F. Jones’ grave

Woodlawn Cemetery, Detroit

James F. Jones was born in Birmingham, Ala., in 1907. As a teenager, he began preaching the gospel, and by 1938 had moved to Detroit to create what would become the Church of Universal Triumph, Dominion of God, Inc. By the 1940s, he had declared himself “Prophet” Jones, and preached that God spoke directly to him. Parishioners were required to take part in all-night worship services, and to celebrate his birthday as a religious holiday. He delivered his sermons via radio and his career presaged the televangelists of later years. His private life was luxurious, and he lived in a three-story mansion on Ferry Street. He was finally felled by a heart attack in 1971. His grave, a surprisingly modest laid stone, is in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Photo via FindaGrave.com

Woodlawn Cemetery, Detroit

James F. Jones was born in Birmingham, Ala., in 1907. As a teenager, he began preaching the gospel, and by 1938 had moved to Detroit to create what would become the Church of Universal Triumph, Dominion of God, Inc. By the 1940s, he had declared himself “Prophet” Jones, and preached that God spoke directly to him. Parishioners were required to take part in all-night worship services, and to celebrate his birthday as a religious holiday. He delivered his sermons via radio and his career presaged the televangelists of later years. His private life was luxurious, and he lived in a three-story mansion on Ferry Street. He was finally felled by a heart attack in 1971. His grave, a surprisingly modest laid stone, is in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Photo via FindaGrave.com

7 of 9

Dante Alighieri

Near Vista and Central avenues, Belle Isle Park, Detroit

Why is there a bust of the author of The Divine Comedy on Belle Isle? It’s yet another statue erected by Detroit’s Italian-American community.It was timed to coincide with the 600th anniversary of the Italian poet’s death, and since Dante was almost universally loved and respected, taught as “littra-chaw” in universities, it was likely a bid for respectability from an immigrant group vying for respectability.

Photo via ItalianiDetroit.wordpress.com

Near Vista and Central avenues, Belle Isle Park, Detroit

Why is there a bust of the author of The Divine Comedy on Belle Isle? It’s yet another statue erected by Detroit’s Italian-American community.It was timed to coincide with the 600th anniversary of the Italian poet’s death, and since Dante was almost universally loved and respected, taught as “littra-chaw” in universities, it was likely a bid for respectability from an immigrant group vying for respectability.

Photo via ItalianiDetroit.wordpress.com

8 of 9

Orville Hubbard

Dearborn Historical Museum, South Brady Street, south of Garrison Street, Dearborn In the 1980s, putting up a statue of longtime Dearborn Mayor Orville Hubbard didn’t seem like a big deal. The larger-than-life mayor held the record for the longest- serving mayor of any U.S. city, a record that remains unbroken today. But as later critics pointed out, the statue had the effect of lionizing a person whose main claim to fame was favoring government-promoted segregation. Well-meaning Dearbornites moved the statue to the city’s historical museum in 2015, thinking that taking the statue off the city’s main drag would deaden the controversy. Finally, after several years of people pointing out that the statue was still displayed as if a point of pride, in December 2017 a plaque accompanying the statue gave the meekest acknowledgement of Hubbard’s racism.

Photo via ArabAmericanNews.com

Dearborn Historical Museum, South Brady Street, south of Garrison Street, Dearborn In the 1980s, putting up a statue of longtime Dearborn Mayor Orville Hubbard didn’t seem like a big deal. The larger-than-life mayor held the record for the longest- serving mayor of any U.S. city, a record that remains unbroken today. But as later critics pointed out, the statue had the effect of lionizing a person whose main claim to fame was favoring government-promoted segregation. Well-meaning Dearbornites moved the statue to the city’s historical museum in 2015, thinking that taking the statue off the city’s main drag would deaden the controversy. Finally, after several years of people pointing out that the statue was still displayed as if a point of pride, in December 2017 a plaque accompanying the statue gave the meekest acknowledgement of Hubbard’s racism.

Photo via ArabAmericanNews.com

9 of 9

Related Slideshows

- Local Detroit

- News & Views

- Things to Do

- Arts & Culture

- Food & Drink

- Music

- Weed

- Detroit in Pictures

- About Metrotimes

- About Us

- Advertise

- Contact Us

- Jobs

- Staff

- Big Lou Holdings, LLC

- Cincinnati CityBeat

- Detroit Metro Times

- Louisville Leo Weekly

- St. Louis Riverfront Times

- Sauce Magazine